Paternal care

Paternal care

Relationships created by male and female members are significant for infant survival in Chacma baboons (Papio ursinus) because the risk of infanticide in early infancy is higher in this species. Paternal care in the form of protection for the infant is therefore more beneficial than long term investment in Chacma baboons and is believed to be directed towards both biological and non-biological infants in the group. The selection pressures that determine the reproductive strategy, and therefore much of the life history, of an organism can be understood in terms of r/K selection theory. The central trade-off to life history theory is the number of offspring vs. the timing of reproduction. Organisms that are r-selected have a high growth rate (r) and tend to produce a high number of offspring with minimal parental care; their lifespans also tend to be shorter.

Critics proposed that females might be more subject to sexual selection than males, but not in all circumstances. While evolutionary psychology hypotheses are difficult to test, evolutionary psychologists assert that it is not impossible. Part of the critique of the scientific base of evolutionary psychology includes a critique of the concept of the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptation (EEA). Some critics have argued that researchers know so little about the environment in which Homo sapiens evolved that explaining specific traits as an adaption to that environment becomes highly speculative.

One study of this species found that fathers had larger hindlimb muscles than did non-breeding males. Quantitative genetic analysis has identified several genomic regions that affect paternal care.

However, actually gaining this optimal life history strategy cannot be guaranteed for any organism. Populations can adapt and thereby achieve an "optimal" life history strategy that allows the highest level of fitness possible (fitness maximization). There are several methods from which to approach the study of optimality, including energetic and demographic. Achieving optimal fitness also encompasses multiple generations, because the optimal use of energy includes both the parents and the offspring. For example, "optimal investment in offspring is where the decrease in total number of offspring is equaled by the increase of the number who survive".

This criticism argues that the longer the time the child needed parental investment relative to the lifespans of the species, the higher the percentage of children born would still need parental care when the female was no longer fertile or dramatically reduced in her fertility. Sexual dimorphism is the difference in body size between male and female members of a species as a result of intrasexual selection, which is sexual selection that acts within a sex. High sexual dimorphism and larger body size in males is a result of male-male competition for females. Primate species in which groups are formed of many females and one male have higher sexual dimorphism than species that have both multiple females and males, or one female and one male. Polygynous primates have the highest sexual dimorphism, and polygamous and monogamous primates have less.

This is a particularly well-documented benefit of parental care that can arise through a variety of mechanisms (reviewed in Clutton-Brock 1991; Alonso-Alvarez and Velando 2012; and Table Table1). Instead, they argue that understanding the causes of rape may help create preventive measures. Franks also states that "The arguments in no sense count against a general evolutionary explanation of psychology." and that by relaxing assumptions the problems may be avoided, although this may reduce the ability to make detailed models. A number of cognitive scientists have criticized the modularity hypothesis, citing neurological evidence of brain plasticity and changes in neural networks in response to environmental stimuli and personal experiences. Neurobiological research does not support the assumption by evolutionary psychologists that higher-level systems in the neocortex responsible for complex functions are massively modular.

In studying humans, life history theory is used in many ways, including in biology, psychology, economics, anthropology, and other fields. For humans, life history strategies include all the usual factors—trade-offs, constraints, reproductive effort, etc.—but also includes a culture factor that allows them to solve problems through cultural means in addition to through adaptation.

Many experts, such as Jerry Fodor, write that the purpose of perception is knowledge, but evolutionary psychologists hold that its primary purpose is to guide action. For example, they say, depth perception seems to have evolved not to help us know the distances to other objects but rather to help us move around in space.

- In order to study these topics, life history strategies must be identified, and then models are constructed to study their effects.

- Generally speaking, r-selected species with their low investment and high fecundity seem particularly well adapted to unpredictable environments that allow fast invasion, maturity, and reproduction.

- Our findings are also consistent with more general life-history theory suggesting that individuals should minimize the time they spend in relatively dangerous life-history stages (Williams 1966; Werner and Gilliam 1984; Werner 1986; Warkentin 2007) and work focused on parental effects.

- Taste and smell respond to chemicals in the environment that are thought to have been significant for fitness in the environment of evolutionary adaptedness.

- The development of upright movement led to the development of females caring for their children by carrying infants in their arms instead of on their backs.

Likewise, parental care will be favored if there are multiple functions of care, such that care increases egg survival and decreases total time spent in the egg stage (Scenario 9), when egg death rate is high (Fig. (Fig.3G) 3G) but not when it is low (Fig. (Fig.3H). In contrast, parental care that increases the total amount of time spent in the egg stage (Scenario 6) is unlikely to be favored, regardless of whether egg death rate is low or high (Fig. (Fig.3A 3A and B).

Sociality may have been a prerequisite for birth attendance, and bipedalism and birth attendance could have evolved as long as five million years ago. Humans have evolved increasing levels of parental investment, both biologically and behaviorally. The fetus requires high investment from the mother, and the altricial newborn requires high investment from a community. Species whose newborn young are unable to move on their own and require parental care have a high degree of altriciality.

Evolutionary Psychology Approach

Male Titi monkeys are more involved than the mother in all aspects of male care except nursing, and engage in more social activities such as grooming, food sharing, play, and transportation of the infant. The bond between an infant and its father is established right after birth and maintained into adolescence making the father the infant's predominant attachment figure. Similarly, the male Owl monkey acts as the main caregiver and is crucial to the survival of his offspring. If a female gives birth to twins, the male is still responsible for transporting both the infants. In the absence of a father, infant mortality increases in both these species and it is unlikely that the infant will survive.

These events, notably juvenile development, age of sexual maturity, first reproduction, number of offspring and level of parental investment, senescence and death, depend on the physical and ecological environment of the organism. Also, fertilization and gestation occur in women, investments which outweigh the male's investment of just one sperm cell.

Most paternal care is associated with biparental care in socially monogamous mating systems (about 81% of species), but in approximately 1% of species, fathers provide all care after eggs are laid. The unusually high incidence of paternal care in birds compared to other vertebrate taxa is often assumed to stem from the extensive resource requirements for production of flight-capable offspring. By contrast, in bats (the other extant flying vertebrate lineage), care of offspring is provided by females (although males may help guard pups in some species).

From the gene's point of view, evolutionary success ultimately depends on leaving behind the maximum number of copies of itself in the population. Until 1964, it was generally believed that genes only achieved this by causing the individual to leave the maximum number of viable offspring. D. Hamilton proved mathematically that, because close relatives of an organism share some identical genes, a gene can also increase its evolutionary success by promoting the reproduction and survival of these related or otherwise similar individuals. Hamilton concluded that this leads natural selection to favor organisms that would behave in ways that maximize their inclusive fitness. It is also true that natural selection favors behavior that maximizes personal fitness.

For example, oysters produce millions of eggs, but most larvae die from predation or other causes; those that survive long enough to produce a hard shell live relatively long. Type I or convex curves are characterized by high age-specific survival probability in early and middle life, followed by a rapid decline in survival in later life. They are typical of species that produce few offspring but care for them well, including humans and many other large mammals. A survivorship curve is a graph showing the number or proportion of individuals surviving to each age for a given species or group (e.g. males or females).

If seen to be of a maladaptive nature, and therefore disregarding the evolutionary psychological evidence for things such as homosexuality, these behaviours can simply be seen in a no different manner than other maladaptations such as poor eyesight. There are three common theoretical explanations for the high levels of paternal care in fish, with the third one currently favoured. First, external fertilization protects against paternity loss; however, sneaker tactics and strong sperm competition have evolved many times. Second, the earlier release of eggs than sperm gives females an opportunity to flee; however, in many paternal care species, eggs and sperm are released simultaneously. Third, if a male is already protecting a valuable spawning territory in order to attract females, defending young adds minimal parental investment, giving males a lower relative cost of parental care.

Grandmothers have evolved mechanisms that allow them to invest in their grandchildren. Menopause might be an adaptation for older women to invest in care of their offspring and their children's offspring. A desire to improve inclusive fitness allows grandmothers, especially maternal grandmothers, to invest the most since they are guaranteed that the child carries their genes. Children without parental care are an extremely vulnerable category, because they are subjected to various risk factors. Therefore, in order to improve health potentials and quality of life, special measures are required in health care, psychological care and social welfare.

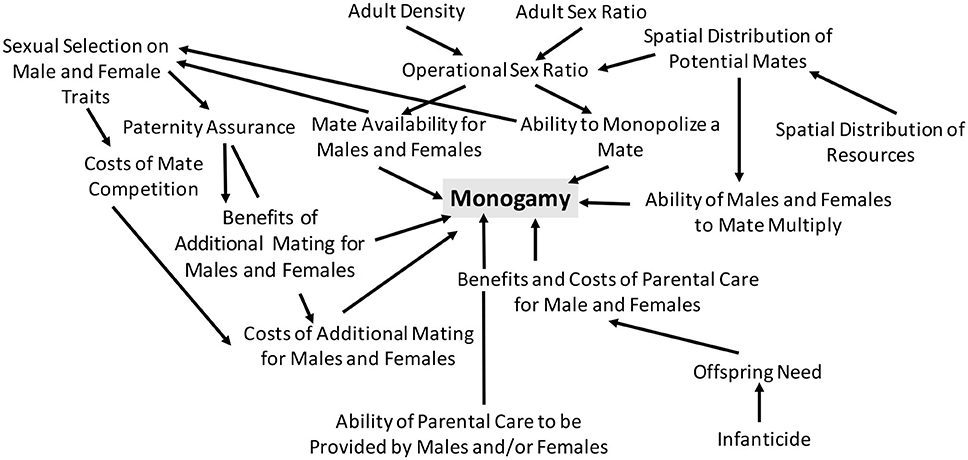

Mating systems influence paternity certainty and the likelihood that a male is providing care towards his own biological offspring. Paternal certainty is high in monogamous pair-bonded species and males are less likely to be at risk for caring for unrelated offspring and not contributing to their own fitness. In contrast, polygamous primate societies create paternity uncertainty and males are more at risk of providing care for unrelated offspring and compromising their own fitness. Paternal care by male non-human primates motivated by biological paternity utilize past mating history and phenotypic matching in order to recognize their own offspring. Comparing male care efforts exhibited by the same species can provide insight on the significant relationship between paternity certainty and the amount of paternal care exhibited by a male.

Комментарии

Отправить комментарий